What is Urethral Trauma?

Injury to the urethra doesn’t happen very often. But this can result from straddle-type falls or pelvic fractures. Dealing with these problems quickly and properly is critical for the best results.

What Happens under Normal Conditions?

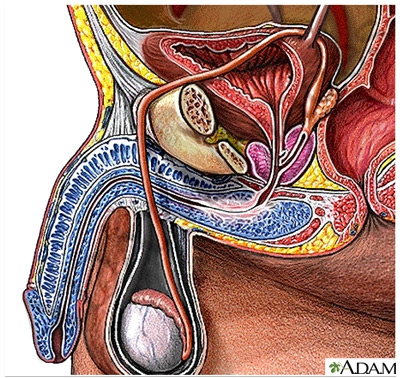

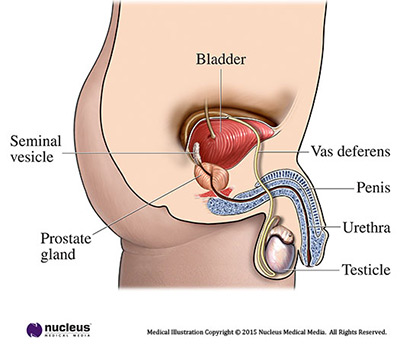

The urethra is a tube-like organ that carries urine from the bladder out of the body. In males, the urethra starts at the bladder and runs through the prostate gland, perineum (the space between the scrotum and the anus), and through the penis. The anterior ("front") urethra goes from the tip of the penis through the perineum. The posterior ("back") urethra is the part deep within the body.

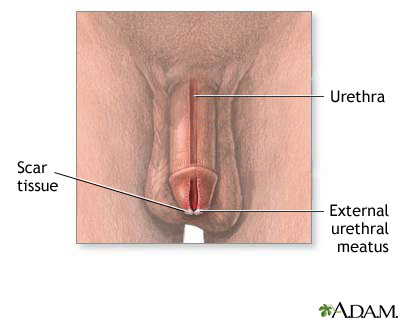

In females, the urethra is much shorter: it runs from the bladder to just in front of the vagina. It opens outside the body. Normal urine flow is painless and can be controlled. The stream is strong and the urine is clear with no visible blood.

What is Urethral Trauma?

Urethral trauma is when the urethra is hurt by force.

Trauma to the anterior urethra is often from straddle injuries. This can occur with a sharp blow to the perineum. This type of trauma can lead to scars in the urethra ("urethral stricture"). These scars can slow or block the flow of urine from the penis.

Trauma to the posterior urethra almost always results from a severe injury. In males, posterior urethral trauma may tear the urethra completely away below the prostate. These wounds can form scar tissue that slows or blocks the urine flow.

For females, urethral injuries are rare. They're always linked to pelvic fractures or cuts, tears, or direct trauma to the body near the vagina.

Urethral injury can also result from objects piercing the sex organs or pelvis.

What Causes Urethral Trauma?

Trauma to the anterior urethra can be caused by straddle injuries—coming down hard on something between your legs, such as a bicycle seat or crossbar, a fence, or playground equipment.

Trauma to the posterior urethra can be caused by pelvic fractures from:

- Car crashes

- Crush injuries

- Falls from very high heights

- Bullets or knives

For females, urethral injuries can also be caused by sexual assault.

How is Urethral Trauma Diagnosed?

If you have blood at the end of the penis or in the urine or can’t pass urine after an injury to the urethral area, you should see a health care provider right away.

Your health care provider may try to pass a tube ("catheter") through your urethra. Not being able to pass a tube into the urethra is the first sign of urethral injury. An x-ray is done after squirting a special dye into the urethra. The dye is used to be seen on an x-ray. X-rays are taken to see if any of the dye leaks out of the urethra inside your body. This would mean there’s an injury. An x-ray of the urethra is often done after a pelvic fracture, because urethral injury is common in these cases (about 1 in 10 cases).

How is Urethral Trauma Treated?

The treatment for urethral trauma depends on where and how bad the injury is. Many cases of anterior urethral injury need to be fixed right away with surgery.

Minor of these injuries can be treated with a catheter through the urethra into the bladder. This keeps urine from touching the urethra so it can mend. The catheter is often left in place for 14 to 21 days. After that time, an x-ray is taken to see if the injury has healed. If it has healed, the catheter can be taken out in the doctor's office. If the x-ray still shows leaks, the catheter is left in longer.

If serious urethral trauma is seen on the x-ray, a tube is used to carry urine away from the injured area to keep it from leaking. Urine leaking inside the body can cause:

- Swelling

- Inflammation

- Infection

- Scarring

The treatment of a posterior urethral injury is very complicated. This is because it's almost always seen with other severe injuries. Unfortunately, it means that this problem can't be fixed right away. Most urologists first place a catheter in the bladder at the time of injury and wait for 3 to 6 months. This gives the body time to reabsorb the bleeding from the pelvic fracture. It's also easier to fix the urethra after swelling in the tissues from a pelvic injury has gone down. Most posterior urethral injuries need an operation to connect the 2 torn edges of the urethra. This is most often done through a cut in the perineum.

If the urethra has completely torn away, urine must be drained. This is done with a tube stuck into the bladder through the skin ("suprapubic"). This Foley catheter goes through the skin just above the pubic bone in the lower belly into the bladder. This is most common after severe injuries. The tube can be put in at the time of abdominal surgery for other repairs. Or it can be done through a small puncture. An x-ray can be used to see that the catheter is in the bladder. Your doctor may suggest a procedure to rejoin the torn urethra over a catheter, which may help it heal.

What Can I Expect after Treatment for Urethral Trauma?

If surgery was done, the catheter left in the bladder can be uncomfortable. Also, the catheter can bother the bladder and cause it to contract on its own, which can hurt. This can also cause some blood to be seen in the urine. These symptoms often clear up after the catheter is taken out.

The most common problem after urethral repair is scarring in the urethra. The scars can partly block the urine flow, causing the stream to be weak. You may also have to strain to urinate. Your urologist can often fix this by widening the scarred section. This is done with instruments placed through the urethra. Sometimes the surgery needs to be done again to keep the urethra open.

If you had a pelvic fracture urethral injury, your urologist will arrange follow-up visits. These are to make sure you don’t develop erectile dysfunction, or urine control problems.

Will I need further surgery after my operation for a posterior urethral injury?

Most patients don’t need further surgery or expansion of urethral scarring after repair.

Will the injury or the surgery cause problems with sex?

Surgery to fix the urethra rarely causes erectile dysfunction. But severe posterior injuries can also harm the delicate nerves that run beside the urethra deep within the body. These nerves send the signal to the penis to become erect for sex. About 5 out of 10 men who have urethral injuries from pelvic fractures will have some type of erectile dysfunction once they heal. This may range from very mild to full erectile dysfunction. But there are many ways to treat this.

Will the injury or the surgery cause me to leak urine?

A small number of patients (2 to 5 out of 100) have problems with incontinence after having posterior urethral trauma fixed. This is thought to be caused by damage to the nerves that control the bladder outlet. This damage is a result of the injury and not from the surgery.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Urethral Stricture Disease?

The urethra's main job in males and females is to pass urine outside the body. This thin tube also has an important role in ejaculation for men. When a scar from swelling, injury or infection blocks or slows the flow of urine in this tube, it is called a urethral stricture. Some people feel pain with a urethral stricture.

What Happens under Normal Conditions?

The bladder empties through the urethra and out of the body (called voiding). The female urethra is much shorter than the male's. In males, urine must travel a longer distance from the bladder through the penis.

In males, the first 1" to 2" of the urethra that urine passes through is called the posterior urethra. The posterior urethra includes:

- the bladder neck (the opening of the bladder)

- the prostatic urethra (the part of the urethra by the prostate)

- the membranous urethra

- a muscle called the external urinary sphincter

Strictures that happen in the first 1" to 2" of the urethra that urine passes through are called posterior strictures.

In males, the final 9" to 10" of the urethra is called the anterior urethra. The anterior urethra includes:

- the bulbar urethra (under the scrotum and perineum- the area between the scrotum and anus)

- the penile urethra (along the bottom of the penis)

- the meatus (the exit at the tip of the penis)

Strictures that happen in the last 9" to 10" of the urethra that urine passes through are called anterior strictures.

What are Symptoms of Urethral Strictures?

Simply put, the urethra is like a garden hose. When there is a kink or narrowing along the hose, no matter how short or long, the flow is reduced. When a stricture is narrow enough to decrease urine flow, you will have symptoms. Problems with urinating, UTIs, and swelling or infections of the prostate may occur. Severe blockage that lasts a long time can damage the kidneys.

Some signs are:

- bloody or dark urine

- blood in semen

- slow or decreased urine stream

- urine stream spraying

- pain with urinating

- abdominal pain

- urethral leaking

- UTIs in men

- swelling of the penis

- loss of bladder control

How are Urethral Strictures Diagnosed??

There are several tests to determine if you have a urethral stricture including:

- physical exam

- urethral imaging (X-rays or ultrasound)

- urethroscopy (to see the inside of the urethra)

- retrograde urethrogram

Urethroscopy

The doctor gently places a small, bendable, lubricated scope ( a small viewing instrument) into the urethra. It is moved up to the stricture. This lets the doctor see the narrowed area. This is done in the office and helps your doctor decide how to treat the stricture.

Retrograde Urethrogram

This test is used to see how many strictures there are, and their position, length and severity. This is done as an outpatient X-ray procedure. Retrograde in this case means "against the flow" of urine. Contrast dye (fluid that can be seen on an X-ray) is inserted into the urethra at the tip of the penis. No needles or catheters are used. The dye lets the doctor see the entire urethra and outlines the narrowed area. It can be combined with an antegrade urethrogram (antegrade means "with the flow" of urine). Dye inserted from below fills the urethra up to the injured area. Dye inserted from above fills the bladder and the urethra down to the stricture. These tests together let the doctor find the gap to plan for surgery.

Also, if you have trauma to the urethra, you may have this X-ray procedure after emergency treatment. Contrast dye can be injected through the catheter that was placed for healing.

How Can Urethral Strictures be Prevented?

- Avoid injury to the urethra and pelvis.

- Be careful with self-catheterization

- Use lubricating jelly liberally

- Use the smallest possible catheter needed for the shortest time

- Avoid sexually transmitted infections.

- Gonorrhea was once the most common cause of strictures.

- Antibiotics have helped to prevent this.

- Chlamydia is now the more common cause.

- Infection can be prevented with condom use, or by avoiding sex with infected partners.

- If a problem occurs, take the right antibiotics early. Urethral strictures are not contagious, but sexually transmitted infections are.

How are Urethral Strictures Treated?

There are many options depending on the size of the blockage and how much scar tissue is involved.

Treatments include:

- dilation – enlarging the stricture with gradual stretching

- urethrotomy – cutting the stricture with a laser or knife through a scope

- open surgery – surgical removal of the stricture with reconnection and reconstruction, possibly with grafts (urethroplasty)

There are no available drugs to help treat strictures.

Without treatment, you will continue to have problems with voiding. Urinary and/or testicular infections and stones could develop. Also, there is a risk of urinary retention (when you can't pass urine), which could lead to an enlarged bladder and kidney problems.

What Can Be Expected after Treatment?

Because urethral strictures can come back after surgery, you should be followed by a urologist. After the catheter is removed, your doctor will want to check you with physical exams and X-rays as needed. Sometimes the doctor performs urethroscopy to check the repair. In some patients, the stricture may return but may not need additional treatment. But if it causes obstruction, it can be treated with urethrotomy or dilation. Repeat open surgery may be needed for serious strictures that come back.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Urethral Diverticulum?

Urethral diverticulum (UD) is a pocket or pouch that forms along the urethra. Because of its location, it can be filled with urine and lead to infections. It is can cause:

- A painful vaginal mass

- Ongoing pelvic pain

- Many urinary tract infections (UTI)

It is rare, but more common in women between age 40 and 70. Children are not usually affected, unless they've had urethral surgery.

With better imaging, more UDs have been found and treated. Still, many cases are missed or misdiagnosed simply because no one considered it.

What are the Symptoms of UD?

Up to 20% of patients with UD may not have clear signs. Symptoms are different for everyone, but the most common are:

- Bladder or UTIs that return

- Pelvic pain

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (similar to an overactive bladder)

- Nocturia (feeling the need to urinate several times at night)

- Pain with sex

- Dribbling

- Blood in the urine

- Vaginal discharge

- Urinary blockage

- Trouble emptying the bladder

- Accidental loss of urine (incontinence)

Some women have a tender area or mass at the front vaginal wall. With a gentle press, urine or pus may show through the urethral opening.

It is important to note that the size of the UD doesn’t matter. In some cases, a very large UD may cause only minor symptoms. Or a small UD may still cause pain. Symptoms can also go away and come back.

How is UD Diagnosed?

Because UDs do not have clear signs, they can be found during an exam or imaging test. In some people, it can be years before the correct diagnosis is made. Patients are often misdiagnosed and treated for other things first.

A proper diagnosis can be made with:

- An in-depth health history

- Physical exam

- Urine studies

- Direct exam of the bladder and urethra (with an endoscope, or tube-like test with a light)

- Imaging tests, such as an MRI or Ultrasound

Physical Exam

When a UD is found, the urologist may “milk” the sac to try to remove pus or urine. In women, the front vaginal wall may be felt for masses and soreness.

Imaging

Many imaging tests can be used to find UD. No single test is best. Each has pros and cons. The final choice often depends on:

- Whether the test is available

- How much it costs

- The skill of the radiologist

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

This type of test uses radio waves and a magnetic field to look closely at the urinary tract. It has the best record of finding a UD. For more information on MRI please visit our UH.org article.

Ultrasound

Using sound waves, this test may show a UD, but would need a follow-up MRI to be sure. For more information on ultrasounds please visit our UH.org article.

Urodynamic Studies

These tests measure lower urinary tract function. They may find stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (accidental loss of urine caused by pressure on the bladder) from a UD. For more information on urodynamics please visit our UH.org article.

Videourodynamic studies (that add imaging) may be able to tell why SUI is happening.

How is UD Treated?

Counseling and Monitoring

Surgery is the main way to treat UD. Still, not all cases call for surgery. Some patients may not want it, or be able to have surgery.

Not much is known about untreated UD. It is not known if the pockets will become larger or if symptoms will get worse. Some people prefer to wait until symptoms get worse before doing anything. In rare cases there have been reports of cancers growing in people with UD.

If you prefer not to have surgery, counseling and follow-up visits with your doctor is important.

Surgery

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. It should be performed with care with an experienced urologist. The UD sac may be attached to the urethral opening. If the sac is not removed carefully, it could damage the urethra. This would lead to a major surgical repair.

Surgical options are:

- Cutting into the sac neck

- Creating a permanent opening of the sac into the vagina

- Removing the sac

Other Key Issues in Surgery

- The diverticular neck (the connection to the urethral opening) should be closed.

- The lining of the diverticular sac should be fully removed to prevent the UD from coming back.

- A closure with many layers is needed so a new opening doesn’t form between the urethra and vagina.

If you have stress urinary incontinence (SUI), a procedure to fix the leaking may be done at the same time as fixing the diverticulum.

What Can Be Expected After Treatment?

If you choose not to have surgery, you should still see your urologist for follow-up care.

If you have surgery:

- You will have antibiotics for at least 24 hours.

- You will be sent home with a catheter in place for 2-3 weeks.

- You may have bladder spasms, which can be managed with drugs.

Two to 3 weeks after surgery, a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG, an x-ray using dye) will be done.

- If there is no fluid leaking, the catheter will be removed.

- If fluid is seen, repeat VCUG will be done weekly until leaking ends.

- In most cases the leaking will end in a few weeks.

Common issues after surgery are:

- UTIs

- Accidental loss of urine

- UD that comes back

- Ongoing symptoms

- Urethrovaginal fistula (an abnormal passage between the urethra and vagina, which is a serious problem that needs treatment)

If UD returns, it may be due to a few things. For example: the pouching is not completely removed, the opening is not completely sealed, remaining dead space, or other technical issues. Repeat surgery can be difficult. This surgery requires a high level of technical skill.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Testicular Trauma?

The testicles are vital for reproduction and normal male hormones. Because they're in the scrotum, which hangs outside the body, they don't have muscles and bones to protect them like most organs have. This makes it easier for the testicles to be struck, hit, kicked, or crushed. Timely evaluation and proper treatment are critical for the best outcomes.

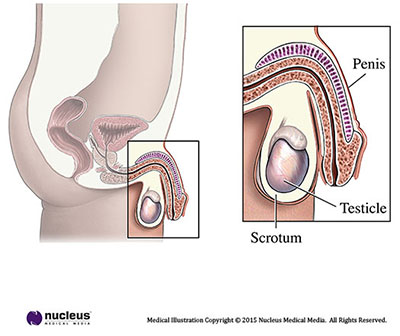

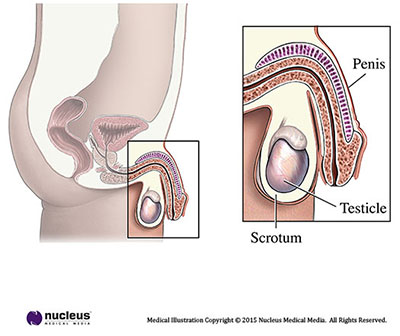

What Happens under Normal Conditions?

The testicles are 2 male organs that make sperm and male hormones. They're in the scrotum, the skin sac that hangs below the penis. Each testicle is encased in a tough, fibrous cover (the tunica albuginea) that protects it.

Sperm cells are made in the testicle and travel to the epididymis, a rubbery gland along the back of the testicle. In the epididymis, thousands of sperm-making ducts from the testicle join to form a single coiled tube. Sperm stop briefly in the epididymis to mature before mixing with semen and leaving through a tube (the vas deferens) that joins with the urethra. The vas deferens is covered by a thick muscle wall. But the epididymis has a thin, fragile coating, and so is at higher risk for swelling or injury.

Testicular Trauma

Testicular trauma is when a testicle is hurt by force. Trauma to the testicle or scrotum can harm any of its contents. When the testicle's tough cover is torn or shattered, blood leaks from the wound. This pool of blood stretches the scrotum until it's tense, and can lead to infection.

What are the Symptoms of Testicular Injury?

The first sign of trauma to the testicle or scrotum is most often severe pain. Pain around the testicle may also be due to infection or swelling of the epididymis ("epididymitis"). Because the epididymis has a very thin wall, it easily becomes red and swollen by infection or injury. If not treated, in rare cases the blood supply to the testicle can get blocked. This can lead to loss of the testicle.

Men who suffer more than a minor injury to the scrotum should seek care by a urologist. Reasons to seek medical care are:

- any penetrating injury to the scrotum

- bruising and/or swelling of the scrotum

- trouble peeing or blood in the urine

- fevers after testicular injury

Though not linked to the injury, a large number of testicular tumors are found after minor injuries when men are more likely to carefully check their testicles. Many men don't notice the painless, solid lump bulging from the smooth testicular cover until they have a reason to look. Even if you think this is a simple bruise, it's a medical emergency. Testicular cancer caught early can often be cured. But tumors found late often need drawn-out treatment with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

What Causes Testicular Injury?

Testicular injuries can be caused by penetrating forces (such as stab wounds or gunshot wounds) or blunt forces (such as a kick or baseball to the scrotum). These can cause all or part of the testicle to rip, as well as loss of the whole testicle. An injury from a penetrating object, such as a knife or bullet that punctures the scrotum, may cause a minor scrape to the skin or major damage to the blood vessels to the testicle. An injury caused by a direct blow can tear the cover of the testicle or harm its blood vessels.

How is Testicular Trauma Diagnosed?

Your urologist can often figure out how bad the injury to the testicle is with a physical exam. After asking questions about how the injury occurred, as well as other questions about your health, he/she will look at your scrotum. It's often easy for your urologist to feel the tough testicle cover, as well as the thin, soft epididymis. He/she will also feel the structures that run into the testicle--the artery, vein and vas deferens--to make sure they're normal.

If all seem normal with no injury, your urologist will likely give you pain meds, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. You'll also be told to wear a jock strap to support the scrotum.

If it's not clear if injury has occurred, your urologist may ask for a scrotal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound uses sound waves bouncing off organs to make a picture of what's inside your body. Based on the same sonar sound waves that guide submarines, this device can safely image parts of the sac, including the testicle, epididymis and spermatic cord, to check the blood flow.

Though no imaging test is 100% perfect, ultrasound is easy to do, uses no X-rays, and clearly shows the structure of the scrotum. In rare cases, the ultrasound leaves more questions than answers. Your urologists may ask for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a more sophisticated imaging technique.

How are Testicular Injuries Treated?

If any imaging study suggests testicular injury, the usual course of action is surgery. Under anesthesia, a cut is made in the scrotum and the contents are checked. If the testicle has torn, it can be repaired if it has good blood supply and the other testicle has enough of its cover. Your urologist will most often fix the tear with stitches and close the scrotum skin. In some cases, he/she will leave a plastic tube in the scrotum for a short time to drain blood and other fluids.

Sometimes an injury is so bad the testicle can't be fixed. In this case, your urologist will remove the testicle. This doesn't mean you can't father a child, though. Only 1 working testicle is needed for normal fertility. A single testicle will most often make normal amounts of sperm and testosterone. If your other testicle is normal, you should be able to get your partner pregnant.

If your physical exam and ultrasound suggest the injury has caused epididymitis, you'll likely be treated without surgery. You may be given anti-inflammatory meds (such as ibuprofen) and again be told to wear a jock strap. If needed, your urologist may also give you an antibiotic. It takes about 6 to 8 weeks for the swelling to go away. You may have to have many follow-up visits with your urologist to chart your progress. If conservative measures (meds and jock strap) don't work, surgery may be needed and the testicle may have to be removed.

Frequently Asked Questions

I've noticed pain in my scrotum and testicle but I don't remember any injury. What should I do?

There are many possible causes of scrotal or testicle pain, such as epididymitis, swelling of the testicle, and problems with other parts of the scrotum. You should be checked by a urologist to find the source.

I was hit by a knee during a basketball game and have since noticed a new lump in my scrotum. It doesn't hurt, but should I do anything about it?

Like many young men, you're likely checking yourself for the first time now that you've had a sporting injury. There's a good chance that the lump or "new" mass you've just felt is a normal part of the anatomy (your epididymis). But it could be an injury or even testicular cancer. Any new lump should be checked at once by a trained urologist. With his/her skill, a urologist will ease your mind and point you to swift and proper treatment.

I'm 55 years old and noticed a lump in my scrotum after being hit in the groin during a pick-up game of baseball. Could this be testicular cancer, or am I too old for that?

Testicular cancer can show up at any age, though most cases are seen between 15 and 35 years of age. Any man with a new lump in his scrotum should see a urologist right away. Often, you won't need any further tests because your urologist can make a diagnosis with a physical exam. He/she may also ask for an ultrasound, though. While some masses are safe (benign), many can be cancer (malignant). The good news is that testicular cancer caught early can be treated with good results. Don't be afraid to call a urologist.

I noticed blood in my urine after being hit with a baseball. I don't feel any lumps. Should I still report this to my urologist?

Absolutely. Blood in the urine that's visible to the naked eye is almost always due to a urological problem. You need to see a urologist right away to find the reason.

What can I do to prevent injury to my testicles?

There are many common-sense steps you can take to lower your risk of testicular trauma. Wear a seat belt when driving a car. If you work around machinery that has exposed chains or belts, make sure your clothes are tucked in and loose belts or other items that can catch aren't exposed. Wear a jock strap when playing sports. If the activity has a chance of rough contact (as in baseball, football, or hockey), use a hard cup.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Penile Trauma?

While the penis is one of the least harmed organs, accidents can happen. Though not common, large hospitals may see a number of cases of penile injuries each year.

How Does the Penis Normally Work?

The main roles of the penis are to carry urine and sperm out of the body. There are 3 tubes inside the penis. One is called the urethra. It is hollow and carries urine from the bladder through the penis to the outside. The other 2 tubes are called the corpora cavernosa. These are spongy tubes that are soft until filled with blood during an erection. The 3 tubes are wrapped together by a very tough fibrous sheath called the tunica albuginea. The urethra acts as a channel for semen to be ejaculated.

What are the Causes and Signs of Penile Injury?

The penis is hurt much less often than other parts of the body. It can be wounded as a result of:

- car accidents

- machine accidents

- gunshot wounds

- burns

- sex

- sports

The penis is most often hurt during sex. Injury to the penis is rare when it isn't erect because it is flexible. During an erection, blood flow in the arteries makes the penis firm. During forceful thrusting, the erect penis may strike the partner and sustain trauma. The penis may then bend sharply despite the erection. You may feel a sharp pain in the penis and maybe hear a "popping" sound. This is often followed by a rapid loss of the erection. The pain and sound are made by a tear in the tunica albuginea, which is stretched tightly during an erection. Urologists often call this injury a penile "fracture," even though there is no bone in the penis. The pain may last for a short time or it may continue. Blood can build up under the skin of the penis (hematoma), and may become swollen and badly bruised. Blood at the tip of the penis or in the urine is a sign of a serious injury to the urethra.

Placing a rubber tube or other constricting device around the base of the penis that is too tight or left on for too long can also injure the penis. Rings or other stiff objects (such as plastic or metal) should never be placed around the penis. These objects can become stuck if the penis swells further. These items can cause lasting damage to the penis if the blood flow is blocked for too long. The urethra and/or penis may also be damaged if objects are put into the tip of the penis.

How are Injuries to the Penis Diagnosed?

If you've injured your penis, your urologist will ask you about your medical history and perform a physical exam, along with blood and urine tests. The goal is to gauge the damage to the penis.

Your urologist may gently place a fiber optic camera into your urethra to check for damage. You might also have an X-ray study called a "retrograde urethrogram."

This is performed by injecting a special dye through the urethra and then taking X-rays. If the X-ray shows the dye leaking outside the urethra, it may suggest damage to that part of the urinary tract. Your urologist might also want to see images of the inside of your penis by ultrasound (sound waves) or MRI (radio waves in a strong magnetic field).

How are Injuries to the Penis Treated?

For Damage Caused by Sex

The treatment for a penis “fractured” during sex is most often surgery. This treatment has lower rates of erectile dysfunction, and penile scarring and curvature. Surgery is done under anesthesia so no pain is felt. The most common surgery is to make a cut around the shaft near the head of the penis and pull back the skin to the base to check the inner surface. The surgeon will then remove blood clots to help find any tears in the tunica albuginea. Any tears are repaired before the skin is sewn back together. A catheter (a thin tube) may be placed through the urethra into the bladder to drain urine and allow the penis to heal. With the whole penis bandaged, you may stay in the hospital for 1 or 2 days. You may go home with or without the catheter. You may be given antibiotics and pain meds. Your surgeon will want to follow up with an office visit to check on healing.

For Serious Trauma

For the rare cases where part of the penis has been accidentally cut off, the amputated part should be wrapped in gauze soaked in sterile salt solution and placed in a plastic bag. The plastic bag should then be put into a second bag or cooler with an ice water slush. Do not place any amputated organ into ice water, as the water and direct contact with ice is harmful to tissue. If the penis can be reattached, the lower temperature of the slush will increase the chances of success. It may be possible to reattach the penis even after 16 hours.

For massive injuries to the penis, urologists who are skilled at this surgery can often rebuild the penis. How well the penis will work after the surgery depends on how badly it was damaged.

What Can I Expect after Treatment for Injuries to the Penis?

Most cases of fractured penis caused by sex and most other minor penile wounds will heal without problems if treated at once. Still, problems can and do happen. Some problems are:

- Infection

- Erectile dysfunction (due to blockage of the nerve or blood flow to the penis)

- Priapism (the penis becomes stiff and stays hard to the point of pain)

- Curved penis (Peyronie's disease) after the wound has healed

How Can I Prevent Penile Injury?

In most cases, injuries to the penis caused by sex can be prevented if your partner is simply aware that it can happen. Most often, penile "fractures" occur with the female partner on top. If your penis is stiff and slips from your partner, stop the thrusting at once.

Other penile injuries can be avoided by using care on the job (especially near machinery), defensive driving and gun safety.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

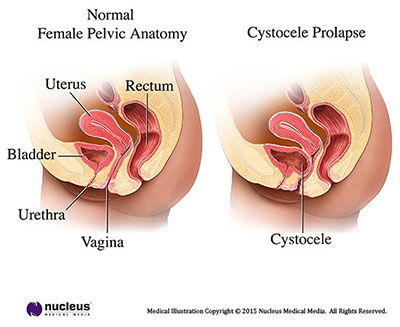

What is Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Under normal conditions in women, the pelvic organs are held in place by a "hammock" of supportive pelvic floor muscles and tissue. When these tissues are stretched and/or become weak, pelvic organs can drop and bulge through this layer and into the vagina.

A cystocele is when the bladder drops and pushes into the vagina. A uterine prolapse is when the uterus drops and pushes into the vagina. A rectocele is when the rectum pushes into the vagina. An enterocele is when the small bowel falls and pushes into the vagina.

In severe cases, the prolapsed organ or organs push the vaginal lining into the opening of the vagina. Sometimes it can even protrude (drop) through the vaginal opening. Pelvic organ prolapse is common in women. The symptoms can be bothersome but it can be treated.

What are the Symptoms of Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

The most common symptom is the feeling of a vaginal bulge. A bulge in the vagina is something you can see or feel.

Other signs and symptoms that may be related to prolapse are:

- frequent voiding or the urge to pass urine

- urinary incontinence (unwanted loss of urine)

- not feeling relief right after voiding

- frequent urinary tract infections

- pain in the vagina, pelvis, lower abdomen, groin or lower back

- heaviness or pressure in the vaginal area

- sex that is painful

- tissue sticking out of the vagina that may be tender and/or bleeding

- Some cases of prolapse may not cause any symptoms.

What Causes Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Prolapse can develop for many reasons. The major cause is stress on this supportive "hammock" when giving birth. Women who have many pregnancies, deliver vaginally, or have long or difficult childbirth are at higher risk.

Other factors that can lead to prolapse are:

- heavy lifting

- chronic coughing (or other lung problems)

- constipation

- frequent straining to pass stool

- obesity

- menopause (when estrogen levels start to drop)

- prior pelvic surgery

- aging

How is Pelvic Organ Prolapse Diagnosed?

Prolapse can be found with a clinical history and a pelvic exam. The exam may be done while you are lying down, straining or pushing, or standing. Your health care provider may measure how serious the prolapse is and what parts of the vagina are falling.

Other tests and imaging studies may also be done to check the pelvic floor, such as:

- cystoscopy

- urodynamics

- x-rays

- ultrasound

- MRI

How is Bladder Prolapse Treated?

Conservative Management

Conservative measures involve

- No treatment. Some women have pelvic organ prolapse and do not have bothersome symptoms. You do not need to treat your prolapse if it is:

- not causing you problems

- not blocking your urine flow

- Behavior therapy this can includes:

- kegel exercises (which help strengthen pelvic floor muscles)

- pelvic floor physical therapy

- a pessary (a vaginal support device)

- Drug therapy this includes:

- estrogen replacement therapy

Surgery

The goal of surgery is to repair your body and improve symptoms. Surgery can be performed through the vagina or the abdomen. There are several ways the surgery can be done, they include:

- Open surgery- when an incision (cut) is made through the abdomen

- Minimally invasive surgery- uses small incisions (cuts) in the abdomen

- Laparoscopic-the doctor places surgical instruments through the abdominal wall

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic- robotic instruments are placed through the abdominal wall. They are attached to robotic arms, and are controlled by the surgeon.

Surgery also involves options of:

- native tissue repair (using one's own tissue and sutures)

- augmentation with surgical material

- polypropylene mesh

- biological graft

Before having surgery you should have an in-depth talk with your surgeon. You should learn about the risks, benefits, and other choices for repairing your prolapse with surgery. It is important that you give informed consent. This can only be done after your doctor has answered all of your questions.

Most commonly, your surgeon will recommend one of two types of surgical repairs for your pelvic organ prolapse.

Sacrocolpopexy is an abdominal surgery that pulls the top of the vagina up by attaching it to a piece of permanent synthetic mesh that is attached to your sacrum. This provides support to the vagina and can keep your pelvic organs in place. In some cases, additional support needs to be provided to certain organs depending on how severe your prolapse is and which organs are involved.

A colpocleisis is a vaginal surgery that brings the walls of the vagina together providing internal support for the pelvic organs, preventing them from falling into the vaginal opening. This procedure is only for women who no longer have vaginal intercourse, as the vaginal opening would be closed after this procedure.

If prolapse is left untreated, over time it may stay the same or slowly get worse. In rare cases, severe prolapse can cause obstruction of the kidneys or urinary retention (inability to pass urine). This may lead to kidney damage or infection.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is a Pelvic Fracture?

Pelvic fractures can result in injury to nearby organs including the lower urinary tract system. High impact traumatic events to the pelvis such as a motor vehicle accident or heavy equipment injury can cause varying degrees of damage to internal organs of the pelvis including the urethra, bladder, prostate and ureters. In some cases the penis and testicles can be involved as well.

In severe cases, high-energy sheering forces or even bone fragments can tear portions of the lower urinary tract. If a portion of the urinary tract is partially torn a Foley catheter may be placed and allow for healing, but if the tearing is complete or severe a suprapubic tube or catheter inserted into the lower abdomen to access the bladder will allow for urine to drain out of the body. In some cases, urine is drained directly out of your kidneys through small tubes placed through the back called nephrostomy tubes.

Pelvic fracture injuries to the lower urinary tract can be repaired with reconstructive surgery. After the pelvis has healed and the swelling has resolved, your surgeon will assess how reconstructive surgery can repair the injured organs. Since every injury is unique, your surgeon will work with you individually to create a surgical plan that best fits your needs.

Urinary Incontinence after Pelvic Fracture

It is not uncommon to have difficulty with urinary incontinence after a pelvic fracture. Depending on which areas of the lower urinary tract were involved in the injury, some patient’s experience varying degrees of unwanted leakage of urine. This is typically a result of damage to the urinary sphincter, surrounding muscles or nerves involved in bladder function. For some people this will improve with time and healing, but for many it can be very bothersome. There are many treatment options for urinary incontinence from medications to an implantable artificial urinary sphincter.

Sexual Dysfunction after Pelvic Fracture

It is very common to have difficulty with erectile dysfunction as well as changes to sensation after a pelvic fracture. The nerves responsible for sexual function are very delicate and can easily be injured during a pelvic trauma. For some people they will regain sexual function over time, but others may not. There are many reliable treatment options available for treating erectile dysfunction from medications to penile implants, depending on the severity of the dysfunction.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Meatal Stenosis?

Sometimes the opening of the penis where urine passes can become blocked. This can cause problems with urination. This article should help you understand this condition and how it can be treated.

How Does the Penis Normally Work?

The main roles of the penis are to carry urine and sperm out of the body. The urethra is the tube that carries urine and sperm through the penis to the outside. The opening to the outside is called the "meatus."

What is Meatal Stenosis?

Meatal stenosis is when the opening at the end of the penis becomes narrow. This condition is usually acquired but can exist from birth.

What are Symptoms of Meatal Stenosis?

The symptoms of meatal stenosis relate to the stream of urine being partly blocked.

These can include:

- Pain or burning while urinating

- Getting sudden urges to urinate ("urgency")

- Needing to urinate often ("frequency")

- A urinary stream that sprays or is hard to aim

- A small drop of blood at the tip of the penis when finished urinating

What Causes Meatal Stenosis?

Meatal stenosis is mostly linked with circumcision and is rarely seen in uncircumcised males. It’s likely that the newly exposed tip of the penis (including the meatus) suffers from a mild injury causing meatus to narrow (stenosis). Uric acid and ammonia crystals are the most common cause for the narrowing of the meatus. These crystals are found in the urine and can be left in the diaper before your baby is changed. These crystals may cause a low grade inflammation which can cause the meatus to narrow over time.

Meatal stenosis can also result from mild ischemia (not enough blood to that part of the body) that occurs during circumcision. Finally, it can also be caused by a mild injury to the tip of the penis as it rubs against the diaper or the child’s own skin after circumcision.

Meatal stenosis can also occur after hypospadias repair. While this isn’t common, it’s seen in up to 1 in 25 patients who have this surgery.

The risk of meatal stenosis is also higher with:

- Injury to the penis tip

- Inflammatory skin conditions (including balanitis and BXO)

- Long-time use of urinary catheters (tubes)

Diagnosis

Meatal stenosis is found by your health care provider with a physical exam. A physical exam will show a small, narrowed meatus. This means the pathway is partly blocked. The lower part of the meatus is often stuck together. There’s no need to measure the opening, as that could cause more harm.

How is Meatal Stenosis Treated?

The best way to treat meatal stenosis is with surgery. The stuck bottom part of the meatus is cut apart. This type of surgery is called a “meatotomy.” After surgery, meatal stenosis rarely comes back as long as proper care is taken.

Meatal stenosis can also be treated by stretching the opening wider (“dilation”). But this can tear the meatus. While this may relieve symptoms for a while, it can cause more scars to form. The new scars make the meatus narrower and cause worse symptoms.

What Can I Expect after Treatment for Meatal Stenosis?

Meatotomy works very well. Pain at the tip of the penis can be helped with oral pain killers or warm baths. Bleeding is rare and usually controlled with direct pressure. Recovery time is fast: typically 1 to 2 days. Spreading lubricating ointment or petroleum jelly on the tip of the penis several times a day for 1 to 2 weeks can ease discomfort and help the wound to heal.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Kidney (Renal) Trauma?

Kidney (renal) trauma is when a kidney is injured by an outside force.

Your kidneys are guarded by your back muscles and rib cage. But injuries can happen as a result of blunt trauma or penetrating trauma.

- Blunt trauma – damage caused by impact from an object that doesn’t break the skin.

- Penetrating trauma – damage caused by an object that pierces the skin and enters the body.

Any type of trauma to the kidney might keep it from working well. It’s important to learn about damage to your kidneys and get immediate care if you need it.

What Happens Under Normal Conditions?

The urinary tract is the body’s drainage system. It includes two kidneys, two ureters, a bladder, and a urethra.

Healthy kidneys work day and night to clean our blood. These 2 bean-shaped organs are found near the middle of the back, just below the ribs. One kidney sits on each side of the spine.

Our kidneys are our body’s main filter. They clean about 150 quarts of blood daily. Every day, they form about 1-2 quarts of urine by pulling extra water and waste from the blood. Urine normally travels from the kidneys down to the bladder and out through the urethra.

As a filter, the kidney controls many things to keep us healthy:

- Fluid balance

- Electrolyte levels (e.g., sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, acid)

- Waste removal in the form of urine

- The regulation of blood pressure and red blood cell counts

When the kidneys are damaged, they may not function well. In most cases, some damage won’t cause too many problems. But, major damage may require more treatment, like dialysis.

What are the Symptoms of Kidney (Renal) Trauma?

Kidney (renal) trauma is when the kidney is hurt by an outside force. There are two types of trauma Blunt and Penetrating Trauma.

Blunt Trauma

The best sign of blunt kidney injury is blood in the urine (“hematuria”). Sometimes the blood can be seen with the naked eye. Other times, it can only be seen through a microscope.

Blunt trauma kidney injuries may show no outside signs. Or bruises may be seen over the back or abdomen where the kidneys are.

Penetrating Trauma

Penetrating kidney trauma may be suspected when there’s a wound from a knife, bullet or other object that has pierced the skin. But sometimes these wounds may be small or hard to find. Also, sometimes the skin wound is far away from the kidney.

What Causes Kidney (Renal) Trauma?

Kidney trauma can occur as kidney injury alone or with other damaged organs. The kidney is the urinary tract organ most often injured by severe trauma.

Blunt trauma can be caused by

- Car accident (children are especially vulnerable to injury in car accidents)

- Fall

- Being hit hard by a heavy object, especially in the flanks (between the rib and the hip)

- An action where the body comes to a sudden stop after moving quickly

Penetrating trauma can be caused by

- Bullet

- Knife

- Any object piercing the body

Kidney injury is rated on a five-grade scale based on how bad it is. Grade one refers to minor injury, such as bruising. Grade five is the most severe, where the kidney is shattered and cut off from its blood supply.

How is Kidney (Renal) Trauma Diagnosed?

A simple dipstick urine test can detect microscopic hematuria.

When kidney injury is suspected, it’s vital to do imaging studies of both kidneys. These will confirm the diagnosis and tell how bad the injury is.

Computerized Tomography

A computerized tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast (a special dye) is the best way to assess kidney injury. A CT scan takes many x-ray images that are put together to show “slices” of parts of the body. Injuries can be seen more clearly as the contrast dye flows through the blood and kidney.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound can also be used to diagnose kidney trauma. Ultrasound uses sound waves bouncing off structures in your body to create images. But it may not show the best details of the injury.

Intravenous Pyelogram

Intravenous pyelogram (IVP) uses x-rays to show how dye moves through your urinary system. IVP can show how the kidneys are working. The dye is injected into a vein in your arm.

How do you Treat Kidney (Renal) Trauma?

Treatment depends on the condition of the patient, how bad the kidney injury is, and if there are other injuries.

If the patient is stable and there’s no injury to other organs, the trauma might be treated without surgery. The patient will rest in the hospital until no more blood is seen in his/her urine. He/she is watched closely for bleeding and other problems. After leaving the hospital, a patient should be watched for signs of kidney damage like late bleeding or high blood pressure.

If a patient isn’t stable and is losing a lot of blood from the kidney, surgery may be done. Surgery can help the doctor get a better look at the injury. The aim of surgery is to fix and preserve the injured kidney. If the patient needs open surgery to repair other organs, the surgeon will check and fix the injured kidney as well. Sometimes a kidney is too badly injured, so it may need to be removed. Fortunately, kidneys are efficient organs and only one healthy kidney is needed for good health.

Today, most kidney injuries are handled without surgery. Many serious injuries can be treated with minimally invasive techniques. One method is angiographic embolization. Using this method, surgeons can reach the arteries of the kidneys through large blood vessels in the groin to stop bleeding.

What are the After Treatments for Kidney (Renal) Trauma?

The most common problems after treatment are leaking urine or delayed bleeding. These may be treated by using telescopes to reach the urinary tract (“endoscopy”) or angiographic embolization. If these things fail, surgery may be needed. The kidney may need to be taken out.

Another problem is a pus pocket (“abscess”) forming around a kidney. This is treated by draining the infection with a tube placed into the abscess. Sometimes surgery is needed to drain the abscess.

Some patients get high blood pressure after major kidney trauma. This may be treated with medication, interventional radiology (including stent placement), or surgery (including removal of the kidney).

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Hypospadias?

Most boys are born with a penis that looks normal and works well. But some boys are born with a common condition called hypospadias. Hypospadias forms a penis that not only doesn't work well but also doesn't look normal. Pediatric urologists have come up with many surgical techniques to fix this problem. The following information should help you speak to your son's urologist.

How Does the Penis Normally Work?

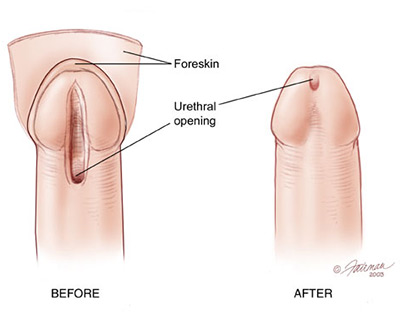

The main roles of the penis are to carry urine and sperm out of the body. The urethra is the tube that carries urine and sperm through the penis to the outside. The opening to the outside is called the "meatus." Both tasks are easier when the meatus is at the tip of the head ("glans") of the penis.

What is Hypospadias?

Hypospadias is a condition where the meatus isn't at the tip of the penis. Instead, the hole may be any place along the underside of the penis. The meatus (hole) is most often found near the end of the penis ("distal" position). But it may also be found from the middle of the penile shaft to the base of the penis, or even within the scrotum ("proximal" positions). Over 80% of boys with this health issue have distal hypospadias. In 15% of those cases, the penis also curves downward slightly, a condition called "chordee." When the meatus opens further down the shaft, curvature occurs in more than 50% of patients. Hypospadias is a common birth defect found in up to 1 in every 200 boys.

In most cases, hypospadias is the only developmental problem in these infants and doesn't imply there are other flaws in the urinary system or other organs.

How is Hypospadias Diagnosed?

Hypospadias is most often noticed at birth. Not only is the meatus in the wrong place, but the foreskin is often not completely formed on its underside. This results in a "dorsal hood" that leaves the tip of the penis exposed. It's often the way the foreskin looks that calls attention to the problem. Still, some newborns have an abnormal foreskin with the meatus in the normal place. And in others a complete foreskin may hide an abnormal meatus. About 8 in 100 of boys with hypospadias also have a testicle that hasn't fully dropped into the scrotum.

How is Hypospadias Treated?

Hypospadias is fixed with surgery. Surgeons have been correcting hypospadias since the late 1800s. More than 200 types of operations have been described. But since the modern era of hypospadias reconstruction began in the 1980s, only a handful of techniques have been used by pediatric urologists.

The goal of any type of hypospadias surgery is to make a normal, straight penis with a urinary channel that ends at or near the tip. The operation mostly involves 4 steps:

- straightening the shaft

- making the urinary channel

- positioning the meatus in the head of the penis

- circumcising or reconstructing the foreskin

What Can I Expect after Treatment?

Modern hypospadias surgery results in a penis that works well and looks normal (or nearly normal). Many surgeons leave a small tube ("catheter") in the penis for a few days after surgery to keep urine from touching the fresh repair. The catheter drains into the diaper. Antibiotics are often given while the catheter is in place.

Younger boys seem to have less discomfort after repair. When the surgery is done at 6 to 12 months of age, as most pediatric urologists recommend, the child doesn't even remember it. Older boys handle this surgery well, also, especially with the types of drugs we now have to treat pain. In some cases, medication may be needed to treat bladder spasms.

Complications

The complication rate in boys with distal hypospadias repair is less than 1 in 10. Problems happen more often after a proximal correction.

The most common problem after surgery is a hole ("fistula") forming in another place on the penis. This is from a new path forming from the urethra to the skin. Scars can also form in the channel or the urethral opening. These scars can interfere with passing urine. If your child complains of urine leaking from a second hole or a slow urinary stream after hypospadias repair, he should see his pediatric urologist.

Most complications appear within the first few months after surgery. But fistulas or blocks might not be found for many years. Most problems are easily fixed with surgery after the tissues have healed from the first operation (often at least 6 months).

It's not easy to think about more surgery in these unusual cases. But there are options that offer hope for success. Unhealthy scarred tissues from prior operations can be removed and replaced with fresh tissue from another part of the body (most often from inside the cheek). This can create a working urinary channel and still look normal. If your pediatric urologist hasn't used these techniques, he/she will direct you to a center where they're used.

Check-ups after Surgery

- Many pediatric urologists believe that routine office check-ups aren't needed after the first few months because the risk for problems past then is so low. Others think boys should be seen throughout childhood until after puberty. You and your son's health care provider will decide what's best.

- circumcising or reconstructing the foreskin

Hypospadias repair is often done in a 90-minute (for distal) to 3-hour (for proximal) same-day surgery. In some cases the repair is done in stages. These are often proximal cases with severe chordee. The pediatric urologist often wants to straighten the penis before making the urinary channel.

Surgeons prefer to do hypospadias surgery in full-term and otherwise healthy boys between the ages of 6 and 12 months. But hypospadias can be fixed in children of any age and even in adults. If the penis is small, your health care provider may suggest testosterone (male hormone) treatment before surgery.

A successful repair should last a lifetime. It will also be able to adjust as the penis grows at puberty.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is hypospadias passed through genes?

In about 7 out of 100 children with hypospadias, the father also had it. The chance that a second son will be born with hypospadias is about 12 out of 100. If both father and brother have hypospadias, the risk in a second boy increases to 21 out of 100.

Is it necessary to fix distal hypospadias?

Many parents ask if surgery is needed for mild forms of hypospadias. It's hard to predict problems a baby will have later in life. But there are many reasons for recommending correction, no matter how severe the condition.

- As many as 15 out of 100 boys with hypospadias will have a penis that curves downward. When the curve is severe, when the boy is an adult it can interfere with getting an effective erection.

- While the meatus may be in a nearly normal place, it's often deformed. Some holes are larger while others are too small. Many have a web of skin just beyond the opening. These abnormalities can affect the urine stream. Some boys will notice urine spraying to the sides or downward. Many find they need to sit to void. Voiding can cause discomfort and irritate nearby tissues. The penis works, but these problems can be embarrassing.

- A partly formed foreskin that isn't fixed will always appear abnormal. This can call attention to the problem. Studies of boys with uncorrected hypospadias suggest lower self-esteem.

Most pediatric urologists today suggest fixing all but the most minor forms of hypospadias. In most cases, the benefits of correction far outweigh its risks.

What kind of anesthesia is used? Is it safe to put infants to sleep?

Hypospadias repair is done while the patient is asleep, under general anesthesia. Many anesthesiologists or surgeons also use nerve blocks near the penis or in the back to reduce discomfort when the child wakes up after surgery. These forms of anesthesia are very safe, especially when given by anesthesiologists who specialize in the care of children. Today, it's thought safe to do surgeries such as hypospadias repair in otherwise healthy infants.

Which repair is best for my son?

The method your son's urologist chooses will depend on a number of factors. These include the degree of hypospadias and how much the penis curves. The surgeon won't know the complete situation until the operation is under way. Surgeons who do hypospadias repair must be familiar with many techniques. Sometimes even a mild distal hypospadias may turn out to need a more complex repair. Most hypospadias repairs are done by pediatric urologists with special training and skill.

How do I care for my son's wound after surgery?

Hypospadias repair wounds don't call for special care to heal the right way. The surgeon may choose from many band age types or not use any at all. The surgeon will instruct you on care of the wound and bathing.

If your son has a catheter, it may be left to drain into diapers. Diapers can be changed as usual. If your son is older, the catheter may be connected to a bag. Your health care provider will teach you how to empty the bag. Catheters are often kept in place for 5 days to 2 weeks.

How long will the healing take?

Wound healing from hypospadias repair starts at once. But it may take many months for it to heal fully. There may be swelling and bruising early on. This gets better over a few weeks. Sometimes the skin of the penis heals with what seems like an unsightly ruffle. There may also be more obvious complications. Any recommendations for more surgery won't be made for at least 6 months, to let the tissues heal. Many slight imperfections will also resolve during this time.

If my child still has problems after many operations, can his hypospadias still be repaired?

Yes. Luckily, most operations are a success the first time. Yet, a few children need more surgery because of complications. Most of them will have good results the second time. Still, a few may have problems that lead to even more surgery. But these problems can be fixed.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is Bladder Trauma?

The bladder isn’t injured often. The bones in the pelvis protect it from most outside forces. But the bladder can be injured by blows or piercing objects. Most often these are related to pelvic fracture. Timely evaluation and proper management are critical for the best outcomes.

What Happens under Normal Conditions?

The bladder is a balloon-shaped organ that stores urine. Its held in place by pelvic muscles in the lower part of your belly. When it isnt full, the bladder is relaxed. Muscles in the bladder wall allow it to expand as it fills with urine. Nerve signals in your brain let you know that your bladder is getting full. Then you feel the need to go to the bathroom. The brain tells the bladder muscles to squeeze (or "contract"). This forces the urine out of your body through your urethra.

What are Symptoms of Bladder Trauma?

The two basic types of damage to the bladder by trauma are bruises and tears.

Blunt injury (a bruise) is damage caused by blows to the bladder. Penetrating injury (a tear) is damage caused by something piercing through the bladder.

Almost everyone who has a blunt injury to the bladder will see blood in the urine. Those with penetrating injury may not actually see bleeding. There may be pain below the belly button, but many times the pain from other injuries makes the bladder pain hard to notice. If there’s a large hole in the bladder and all of the urine leaks into the abdomen, it’s impossible to pass urine. In women, if the injury is severe enough, the vagina may be torn open as well as the bladder. If this happens, urine may leak from the bladder through the vagina. Blood may also come out of the vagina in this case.

Other symptoms may include:

- Hard to start urinating

- Weak urine stream

- Painful urination

- Fever

- Severe back pain

What Can Cause Bladder Trauma?

When the bladder is empty, the bones of the pelvis protect it from blows to the lower abdomen. As it fills, though, the top of the bladder rises into the abdomen where it’s less protected. In children, the pelvic bones aren’t fully developed, so it’s more easily injured than adults. If the pelvis is hit with a force great enough to break the pelvic bones, the bladder may be injured even if it’s empty.

The most common ways the bladder is injured are:

- Car crashes

- Falls from high places

- Heavy object falling on the lower abdomen

You can prevent bladder trauma from a car crash by wearing a seat belt properly. The seat belt should be worn as a lap belt, and not across the belly. During a car crash, passengers with a full bladder wearing a seat belt around the belly may have the force of the crash focus on the full bladder.

The bladder can also be hurt by being pierced from the outside ("penetrating trauma"). Some causes of penetrating trauma are:

- Bullets

- Knives

- Shrapnel

- IEDs (improvised explosive devices)

How is Bladder Trauma Diagnosed?

A health care provider diagnoses bladder injury by placing a tube ("catheter") into the bladder and taking a series of X-rays. X-rays of the urethra may be taken before the catheter is put in, to see if it is damaged. Before the X-rays are taken, the bladder is filled with a liquid that will make it visible on the X-rays.

How is Bladder Trauma Treated?

The treatment for bladder trauma depends on the type of damage.

Blunt injury is damage caused by blows to the bladder. This bruises the bladder.

Penetrating injury is damage caused by something piercing through the bladder. This tears the bladder.

Contusion

Most of the time, the bladder wall doesn’t tear and is only bruised. The only sign will be bloody urine. Your health care provider may just leave a wide catheter in the bladder so clots can pass. Once the urine becomes clear, the catheter will be taken out if there aren’t any other reasons to leave it in.

Intraperitoneal Rupture

If the tear is on the top of the bladder, the hole will usually open to the part of the abdomen that holds the liver, spleen, and bowel. Urine leaking into the abdomen is a serious problem. This tear can be sewn closed with surgery. A catheter is left in the bladder for up to 2 weeks after surgery to allow the bladder to rest. The tube will either come out through the urethra or out through the skin below the belly button.

Extraperitoneal Rupture

If the tear is at the bottom or side of the bladder, the urine will leak into the tissues around the bladder instead of the abdominal cavity. Complex injuries of this type should be repaired with surgery. But often it can be treated by simply placing a wide catheter into the bladder to keep it empty. The urine and blood drain into a collection bag. It usually takes at least 10 days for the bladder to heal. The catheter is left in the bladder until an X-ray shows that the leak has sealed. If the catheter doesn’t drain properly, surgery is needed.

Penetrating Injuries

Injury to the bladder from a bullet or other penetrating object is usually fixed with surgery. Most of the time, other organs in the area will be injured and need repair as well. After surgery, a catheter is left in the bladder to drain the urine and blood until the bladder heals.

What Can I Expect after Treatment?

After the catheter is taken out, urination should return to normal in a few weeks. You'll usually take antibiotics for a few days to get rid of any infection in the bladder from the injury or the catheter. In some patients, the bladder may be "overactive" for many weeks or months from the irritation of the injury. With overactive bladder, you would feel the need to urinate often ("frequency") or suddenly ("urgency"). For this, you may be given drugs to help calm the bladder.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.

What is a Bladder Fistula?

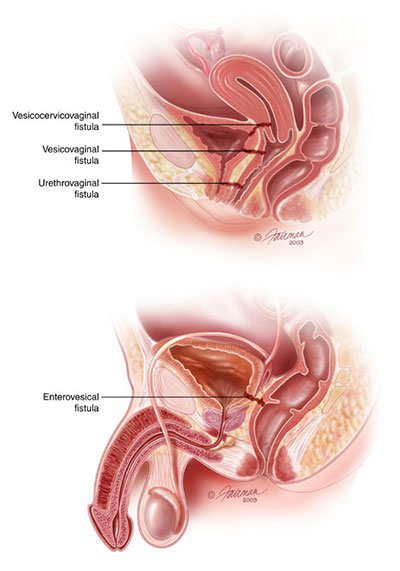

A bladder fistula is when an opening forms between the bladder and some other organ or the skin. Most often the bladder opens to the bowel ("enterovesical fistula") or the vagina ("vesicovaginal fistula").

How Does the Bladder Usually Work?

The bladder is a balloon-shaped organ that stores urine, which is made in the kidneys. It is held in place by pelvic muscles in the lower part of your belly. When it isn't full, the bladder is relaxed. Nerve signals in your brain let you know that your bladder is getting full. Then you feel the need to pee. The brain tells the bladder muscles to squeeze (or "contract").

What are the Signs of Bladder Fistula?

Your health care provider may suspect bladder fistula if you have difficult urinary tract infections. Other signs are urine smelling or looking like stool or if gas comes out through your urethra when you pee.

How is Bladder Fistula Diagnosed?

Bladder fistula is diagnosed with an x-ray study. The type of x-ray used may be a CT scan or a pelvic x-ray. A dye that shows up well in x-rays (called "contrast") will be put into your bladder, either through a vein or a catheter. Your health care provider may also look into your bladder with a cystoscope, a long, thin telescope with a light at the end. In some cases, x-ray studies with contrast may be done on other organs (like the bowel), as well.

How is Bladder Fistula Treated?

Bladder fistula is most often treated with surgery to remove the damaged part of the bladder. Healthy tissue is moved between the bladder and the other organ to block the opening. If the fistula is caused by a disease, such as colon cancer or inflammatory disease, the fistula is fixed during the surgery to treat that disease.

What Can I Expect after Treatment for Bladder Fistula?

The success of the surgery depends on the surgeon being able to remove the main disease. There also must be healthy tissue to close the fistula with. If there is cancer that can't be removed or tissue that has poor blood flow due to radiation treatment, the results might not be as good. After surgery, you can expect to have a catheter in your bladder for a few weeks.

Content provided courtesy & permission of the American

Urological Association Foundation, and is current as of 5/2010.

Visit us at www.urologyhealth.org for additional information.